We are going to continue with our exploration into the history of education for this episode. Although we have some more teacher stories, interviews, and big ideas to share very soon, I figure that as we are on a roll, we should do what we can to do the topic justice.

This podcast is available in iTunes, Google, Spotify, and many other pod catchers. Subscribe with this URL: https://feed.podbean.com/teatimeteaching/feed.xml

Part one:

Before we can discuss the history of education in Ancient Greece, we first must define where end when we are talking about. When we talk about Ancient Greece, we are referring to the civilizations, states, and people who inhabited the Greek peninsula and islands of the Aegean from around the 12th century BCE to the 6th Century AD. During this time, there were several epochs, or ages. The earliest evidence we have of civilizations in the area is from around 12th century BCE with the Minoan civilization. If you are familiar with the stories of the Iliad and the Odyssey, they come from this era. The Mycenean civilization was a literate and complex one, but when it collapsed – and we are not sure how exactly, although natural disaster is likely – so was their writing. What was left behind were a scattering of smaller villages, towns, and cities, usually on the coast, and reliant on trade with other Mediterranean civilizations.

This period between the 8th century BCE, and the 6th Century BCE is sometimes referred to as the Greek Dark Ages. Over this time, the city states, evolved into their own systems, referred to themselves as Polis, and borrowed and adapted the Phoenician alphabet into what we recognize as Greek.

With a script in place, knowledge began to be written down again, and so we have our first historian Herodotus wrote between the 450s and 420s BCE, and his tradition was followed by such as Thucydides, Xenophon, Demosthenes, Plato and Aristotle.

One of the things we need to be aware of when we talk about Ancient Greece is that we are not referring to one Empire or political entity. Effectively Greece was a collection of independent city states geographically cut off from one another by mountains and the sea. It is through trade that knowledge was passed, and ideas spread, but effectively we are talking about areas which evolved their own laws and traditions – for example, Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and Macedonia.

I could spend hours talking about ancient Greece, but we need to focus on our main question. What was education like in classical Greece?

There were some general similarities between city states in Ancient Greece. For example, by the 5th Century BCE there was some “democratization” of education. Most free males could go to a public school, referred to as a gymnasium, while wealthy young men were educated at home by a private tutor. How you were education was a central component of your identity. For example, we know that Alexander the Great was tutored by Aristotle. For most Greeks, education reflected your social status and who you were as a person. We have a similar attitude today, often asking folks where they went to college, or who conferred their degree, as a sign of status and rank.

You will notice that slaves did not have access to an education (in some city-states, slaves were forbidden), and women did not get a formal education (although this varied from city state to city state).

In Athens, until about 420BCE, every free male received an elementary education. This was split into two parts – physical and intellectual. The physical aspect, “gymnastike” prepared citizens for their military service – they were taught strength, stamina, and military tactics. For Athenians, physical fitness was important for both aesthetic and practical reasons. Training was conducted in a “gymnasium” (a word still used to describe some elementary schools in this area today). The intellectual aspect, “mousike” was a combination of music, dance, lyrics, and poetry. Students learned to write with a stylus on wax tablets. When students were ready, they would read, memorize, and recite legends and Homeric stories. In this period, once a boy reached adolescence, his formal education ended.

Around 420 BCE, we begin to see Higher Education in Athens. Philosophers such as Socrates, along with the sophistic movement led to an influx of teachers from all over the Mediterranean. It became fashionable to value intellectual ability over military prowess. This causes a clash between traditionalist, who feared that intellectuals would destroy Athenian culture and lead to a military disadvantage, while sophists believed that education could be a tool to develop the whole man, including his intellect, and therefore move Athens forward. (I’m sure you can think of similar arguments between traditionalists and progressives today – some things never change).

Anyway, the demand for higher education continued and we begin to see more focused areas of study – mathematics, astronomy, harmonics, and dialectic – all with the aim of developing a philosophical insight. For these Athenians, individuals should use knowledge within a framework of logic and reason – what we call today – critical thinking.

However, this level of education was not democratized. Wealth determined your level of education in ancient Athens. These formal programs were taught by sophists who charged for their teaching and advertised for their services, more customers meant more money could be made. So, if you were a free peasant, your access to higher education was limited (something that also resonates today), while women and slaves were excluded from this process altogether. Women were considered socially inferior in Athens and incapable of acting at a high intellectual capacity, while it was dangerous to educate slaves, and in Athens, illegal.

Part Two:

So, who were the sophists? Let’s begin with the most famous – Socrates, or as Bill and Ted call him Socrates. Now the problem with learning about Socrates is that he didn’t write anything down himself. Indeed, most of what we learn about him comes from two of his students: Plato, and Xenophon. Some of their writings about Socrates, particularly Plato’s often contradict themselves. But generally, he is considered the father of philosophy. He advocated that a good man pursues virtue over material wealth, and he mused upon the idea of wisdom. The story goes that he decided to ask every wise man about what they know, and he found that they thought themselves wise, yet they were not, while Socrates himself knew that he was not wise at all, which paradoxically, made him wiser since he was the only person aware of his own ignorance. This stance threatened the status of the most powerful Athenians, so he was eventually tried and when asked what his punishment should be, he proposed free dinners for the rest of his life, as his position as someone who questions Athens into action and progress should be rewarded. Unfortunately, Athenians didn’t see it that way, and he was found guilty of corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, and of “impiety” (not believing in the official gods of the state). As punishment he was sentenced to death by poisoning. Again – we see a similar theme in today’s educational debate, where educational stances that encourage students to question the status quo and take a critical stance are considered threatening to those in power. Some things just don’t change, do they?

Isocrates was a student of Socrates who founded a school of Rhetoric around 393BCE. He believed education’s purpose was to produce civic efficiency and political leadership, therefore the ability to speak well and be persuasive was the cornerstone of his approach. While his students didn’t have to write 5 paragraph persuasive essays, you can see this approach in modern day social studies classes as well as middle and high school English curricula.

Plato, on the other hand, travelled for ten years after Socrates’ execution, returning to establish his Academy, named after the Greek hero Akedemos, in 387 BCE. He believed that education could produce citizens who could cooperate and members of a civic society (like the aims of 19th and 20th century public educators). His curriculum focused on Civic Virtue. The idea that a good citizen would act for the common good, at the expense of their individual gains. In his work “the Republic” he outlines that everyone needs an elementary education in music, poetry, and physical training, two to three years of military training, ten years of mathematics science, five years of dialectic training, and 15 years of practical political training. Those who could attain all that knowledge would become “philosopher kings”, the leaders in his ideal society.

Aristotle was a student of Plato, learning in his academy for 19 years. When Plato died, her travelled until he was invited by Philip of Macedon to educate his 13-year-old son, Alexander (later the Great). In 352 BCE he moved back to Athens to open his school, the Lyceum. Aristotle’s approach was based around research. There was systemic approach to the collection of information, and a new focus on empirical methods, like what we see as the foundation of our modern research methods.

So, these were the developments in Athens, however, this was not the same for all of Greece. Whereas the Athenian system evolved away from a focus on preparation of male citizens for military service, Spartan society kept military superiority as the focus for its education system.

Education in Sparta was focused around what we would probably call a military academy system – called “agoge” in Greek. In general, all Spartan males (except for the first born of the two ruling houses), went through a system which cultivated loyalty to Sparta through military training, hardships, hunting, dancing, singing, and social preparation. It was divided in three age groups, young children, adolescents, and young adults. Spartan girls did not get the same education, although we think there was a formal system for them too.

The three age categories were the paides (7-14), paidiskoi (15-19) and the hebontes (20-29). Within these age groups boys were divided in to agelai (herds) with whom they would sleep (consider these like a house system in British private schools, or the Harry Potter stories). They answered to an older boy, and an official who was the paidonomous, or “boy-herder).

So, the Paides, were taught the basics of reading and writing, but the focus was on their athletic ability. They did running and wrestling, they were encouraged to steal their food, but according to Xenophon, if they were caught, they were punished. Boys participated in the agoge in bare feet, to toughen them up, and at the age of 12 were allowed one item of clothing, a cloak, per year. Around the age of 12, a boy would gain a mentor who was an older warrior, called the “erastes”. As the boy transitioned into the Paidiskoi, so the mentor would act as a sponsor, while the student further developed his physical and athletic training.

By the age of 20, the young Spartan graduated from the paidiskoi into the hebontes. If he had developed leadership qualities, these would be rewarded. At this stage, they were considered adults, they were eligible for military service, and could vote in the assembly, although they were not yet full free citizens. By 30 a Spartan man should have graduated, been accepted into the military, and was permitted to marry. He would also be allocated an allotment of land.

This state education system not only prepared Spartan men for war, but also instilled a strong Spartan identity. They were away from their families for most of their childhood and this likely instilled a sense of favoring the needs of the collective over themselves as individuals or their own families. Indeed, the legend of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae clearly illustrates this concept of individual sacrifice for the collective good.

This Spartan education provides a contrast to Athenian education. In Sparta education was state sponsored, designed to create a citizen who put the collective first. In Athens, higher education was private, and intended to create a citizen who put the collective first by way of virtue. However, Plato intended only a select few to be philosopher-kings, while Sparta expected everyone to be a military citizen.

There is one other aspect of Ancient Greek education that I want to talk about. The symposium. In ancient Greece this was a part of the banquet that took place after the meal, where men would retire to the andron (men’s quarters) recline of couches, and drink, and be entertained, and discuss a multitude of topics. While these were the precursors to the drinking parties that we associate with Ancient Rome, I can see many parallels with academic conferences in the modern day, where scholars share their research in a common location, eat and drink together, and find excuses to sample local entertainments. Of course, the pandemic has curtailed many of these activities, but one day we might be able to meet and talk in person again.

One thing we all have in common is that we’ve been to school. So, if you would like to contribute to the pod in any way, if you have a story to share, long, short, tragic, or comic, if you have comments to make about the podcast, or just want to say “hi”, you can send an email to TeachersTeaTimePod@gmail.com or alternatively you can send emails to me directly using mark@edjacent.org I love to read what you have to say.

If social media is your thing, you can follow me on Twitter @markdiacop.

You can find our contact information, copies of the show notes, and you can download previous episodes of the podcast at www.teachersteatimepod.com

The podcast artwork was created by Phaedra.

Opening and closing music is by Bryan Boyko.

Part One:

Before we can discuss the history of education in Ancient Greece, we first must define where end when we are talking about. When we talk about Ancient Greece, we are referring to the civilizations, states, and people who inhabited the Greek peninsula and islands of the Aegean from around the 12th century BCE to the 6th Century AD. During this time, there were several epochs, or ages. The earliest evidence we have of civilizations in the area is from around 12th century BCE with the Minoan civilization. If you are familiar with the stories of the Iliad and the Odyssey, they come from this era. The Mycenean civilization was a literate and complex one, but when it collapsed – and we are not sure how exactly, although natural disaster is likely – so was their writing. What was left behind were a scattering of smaller villages, towns, and cities, usually on the coast, and reliant on trade with other Mediterranean civilizations.

This period between the 8th century BCE, and the 6th Century BCE is sometimes referred to as the Greek Dark Ages. Over this time, the city states, evolved into their own systems, referred to themselves as Polis, and borrowed and adapted the Phoenician alphabet into what we recognize as Greek.

With a script in place, knowledge began to be written down again, and so we have our first historian Herodotus wrote between the 450s and 420s BCE, and his tradition was followed by such as Thucydides, Xenophon, Demosthenes, Plato and Aristotle.

One of the things we need to be aware of when we talk about Ancient Greece is that we are not referring to one Empire or political entity. Effectively Greece was a collection of independent city states geographically cut off from one another by mountains and the sea. It is through trade that knowledge was passed, and ideas spread, but effectively we are talking about areas which evolved their own laws and traditions – for example, Athens, Sparta, Thebes, and Macedonia.

I could spend hours talking about ancient Greece, but we need to focus on our main question. What was education like in classical Greece?

There were some general similarities between city states in Ancient Greece. For example, by the 5th Century BCE there was some “democratization” of education. Most free males could go to a public school, referred to as a gymnasium, while wealthy young men were educated at home by a private tutor. How you were education was a central component of your identity. For example, we know that Alexander the Great was tutored by Aristotle. For most Greeks, education reflected your social status and who you were as a person. We have a similar attitude today, often asking folks where they went to college, or who conferred their degree, as a sign of status and rank.

You will notice that slaves did not have access to an education (in some city-states, slaves were forbidden), and women did not get a formal education (although this varied from city state to city state).

In Athens, until about 420BCE, every free male received an elementary education. This was split into two parts – physical and intellectual. The physical aspect, “gymnastike” prepared citizens for their military service – they were taught strength, stamina, and military tactics. For Athenians, physical fitness was important for both aesthetic and practical reasons. Training was conducted in a “gymnasium” (a word still used to describe some elementary schools in this area today). The intellectual aspect, “mousike” was a combination of music, dance, lyrics, and poetry. Students learned to write with a stylus on wax tablets. When students were ready, they would read, memorize, and recite legends and Homeric stories. In this period, once a boy reached adolescence, his formal education ended.

Around 420 BCE, we begin to see Higher Education in Athens. Philosophers such as Socrates, along with the sophistic movement led to an influx of teachers from all over the Mediterranean. It became fashionable to value intellectual ability over military prowess. This causes a clash between traditionalist, who feared that intellectuals would destroy Athenian culture and lead to a military disadvantage, while sophists believed that education could be a tool to develop the whole man, including his intellect, and therefore move Athens forward. (I’m sure you can think of similar arguments between traditionalists and progressives today – some things never change).

Anyway, the demand for higher education continued and we begin to see more focused areas of study – mathematics, astronomy, harmonics, and dialectic – all with the aim of developing a philosophical insight. For these Athenians, individuals should use knowledge within a framework of logic and reason – what we call today – critical thinking.

However, this level of education was not democratized. Wealth determined your level of education in ancient Athens. These formal programs were taught by sophists who charged for their teaching and advertised for their services, more customers meant more money could be made. So, if you were a free peasant, your access to higher education was limited (something that also resonates today), while women and slaves were excluded from this process altogether. Women were considered socially inferior in Athens and incapable of acting at a high intellectual capacity, while it was dangerous to educate slaves, and in Athens, illegal.

Part Two:

So, who were the sophists? Let’s begin with the most famous – Socrates, or as Bill and Ted call him Socrates. Now the problem with learning about Socrates is that he didn’t write anything down himself. Indeed, most of what we learn about him comes from two of his students: Plato, and Xenophon. Some of their writings about Socrates, particularly Plato’s often contradict themselves. But generally, he is considered the father of philosophy. He advocated that a good man pursues virtue over material wealth, and he mused upon the idea of wisdom. The story goes that he decided to ask every wise man about what they know, and he found that they thought themselves wise, yet they were not, while Socrates himself knew that he was not wise at all, which paradoxically, made him wiser since he was the only person aware of his own ignorance. This stance threatened the status of the most powerful Athenians, so he was eventually tried and when asked what his punishment should be, he proposed free dinners for the rest of his life, as his position as someone who questions Athens into action and progress should be rewarded. Unfortunately, Athenians didn’t see it that way, and he was found guilty of corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, and of “impiety” (not believing in the official gods of the state). As punishment he was sentenced to death by poisoning. Again – we see a similar theme in today’s educational debate, where educational stances that encourage students to question the status quo and take a critical stance are considered threatening to those in power. Some things just don’t change, do they?

Isocrates was a student of Socrates who founded a school of Rhetoric around 393BCE. He believed education’s purpose was to produce civic efficiency and political leadership, therefore the ability to speak well and be persuasive was the cornerstone of his approach. While his students didn’t have to write 5 paragraph persuasive essays, you can see this approach in modern day social studies classes as well as middle and high school English curricula.

Plato, on the other hand, travelled for ten years after Socrates’ execution, returning to establish his Academy, named after the Greek hero Akedemos, in 387 BCE. He believed that education could produce citizens who could cooperate and members of a civic society (like the aims of 19th and 20th century public educators). His curriculum focused on Civic Virtue. The idea that a good citizen would act for the common good, at the expense of their individual gains. In his work “the Republic” he outlines that everyone needs an elementary education in music, poetry, and physical training, two to three years of military training, ten years of mathematics science, five years of dialectic training, and 15 years of practical political training. Those who could attain all that knowledge would become “philosopher kings”, the leaders in his ideal society.

Aristotle was a student of Plato, learning in his academy for 19 years. When Plato died, her travelled until he was invited by Philip of Macedon to educate his 13-year-old son, Alexander (later the Great). In 352 BCE he moved back to Athens to open his school, the Lyceum. Aristotle’s approach was based around research. There was systemic approach to the collection of information, and a new focus on empirical methods, like what we see as the foundation of our modern research methods.

So, these were the developments in Athens, however, this was not the same for all of Greece. Whereas the Athenian system evolved away from a focus on preparation of male citizens for military service, Spartan society kept military superiority as the focus for its education system.

Education in Sparta was focused around what we would probably call a military academy system – called “agoge” in Greek. In general, all Spartan males (except for the first born of the two ruling houses), went through a system which cultivated loyalty to Sparta through military training, hardships, hunting, dancing, singing, and social preparation. It was divided in three age groups, young children, adolescents, and young adults. Spartan girls did not get the same education, although we think there was a formal system for them too.

The three age categories were the paides (7-14), paidiskoi (15-19) and the hebontes (20-29). Within these age groups boys were divided in to agelai (herds) with whom they would sleep (consider these like a house system in British private schools, or the Harry Potter stories). They answered to an older boy, and an official who was the paidonomous, or “boy-herder).

So, the Paides, were taught the basics of reading and writing, but the focus was on their athletic ability. They did running and wrestling, they were encouraged to steal their food, but according to Xenophon, if they were caught, they were punished. Boys participated in the agoge in bare feet, to toughen them up, and at the age of 12 were allowed one item of clothing, a cloak, per year. Around the age of 12, a boy would gain a mentor who was an older warrior, called the “erastes”. As the boy transitioned into the Paidiskoi, so the mentor would act as a sponsor, while the student further developed his physical and athletic training.

By the age of 20, the young Spartan graduated from the paidiskoi into the hebontes. If he had developed leadership qualities, these would be rewarded. At this stage, they were considered adults, they were eligible for military service, and could vote in the assembly, although they were not yet full free citizens. By 30 a Spartan man should have graduated, been accepted into the military, and was permitted to marry. He would also be allocated an allotment of land.

This state education system not only prepared Spartan men for war, but also instilled a strong Spartan identity. They were away from their families for most of their childhood and this likely instilled a sense of favoring the needs of the collective over themselves as individuals or their own families. Indeed, the legend of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae clearly illustrates this concept of individual sacrifice for the collective good.

This Spartan education provides a contrast to Athenian education. In Sparta education was state sponsored, designed to create a citizen who put the collective first. In Athens, higher education was private, and intended to create a citizen who put the collective first by way of virtue. However, Plato intended only a select few to be philosopher-kings, while Sparta expected everyone to be a military citizen.

There is one other aspect of Ancient Greek education that I want to talk about. The symposium. In ancient Greece this was a part of the banquet that took place after the meal, where men would retire to the andron (men’s quarters) recline of couches, and drink, and be entertained, and discuss a multitude of topics. While these were the precursors to the drinking parties that we associate with Ancient Rome, I can see many parallels with academic conferences in the modern day, where scholars share their research in a common location, eat and drink together, and find excuses to sample local entertainments. Of course, the pandemic has curtailed many of these activities, but one day we might be able to meet and talk in person again.

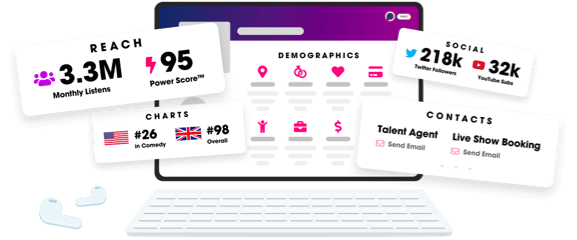

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us