Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

Before we begin, a quick warning. This

0:03

episode contains a brief discussion of a violent

0:05

crime. We don't get into graphic detail,

0:08

but listener discretion is advised. The

0:11

truth is is that the criminal justice

0:14

database infrastructure in the

0:16

United States is terrible. I'm

0:23

Tali Farhadian Weinstein, and this

0:25

is Hearing, and this week I'm

0:27

talking to one of the architects of the Innocence Project,

0:30

Barry Scheck. If you listen

0:32

to the show, I'm willing to bet that's a name

0:35

you've heard before. But even for

0:37

those of us who are familiar with Barry, it's

0:39

easy to forget just how transformative

0:42

a figure he really is. Almost

0:45

thirty years ago, Barry's early

0:47

work in DNA analysis was a

0:49

moonshot one that has since

0:51

led to the exoneration of hundreds

0:53

of wrongfully convicted people. But

0:56

beyond delivering justice to those people

0:58

and their families, the Innocence Project's

1:01

emphasis on DNA had a positive,

1:03

holistic effect on the entire criminal

1:05

justice system. It encouraged

1:08

the spirit of cooperation between prosecutors

1:10

and defense attorneys, pushing us

1:12

to better find and convict the

1:14

people who actually committed the crimes.

1:17

In short, Barry was a pioneer

1:20

in using science to increase public

1:22

safety, and now he wants to

1:24

bring a similar approach to

1:26

policing, which is where those databases

1:29

you just heard him complaining about come

1:31

in. We'll

1:36

get to Barry's latest moonshot in a moment,

1:38

but I wanted to start our conversation by

1:41

asking him to revisit those early days

1:43

of the Innocence Project and one

1:45

case in particular that demonstrated

1:47

the potential of science like DNA

1:50

to revolutionize criminal investigations.

1:54

We got a case that dealt with

1:56

somebody that was convicted in the

1:58

bronx of his

2:00

name was marrying Cokeley of a

2:03

gunpoint rape robbery

2:05

of a couple that was in a motel

2:08

and the guy came into the motel room

2:10

and he locked the guy in a bathroom

2:13

and then he took the woman. He

2:15

sexually assaulted her, and then at

2:17

gunpoint, he took the woman to

2:20

her home, took her car to her

2:22

home, and he grasped

2:25

the rear view mirror of the car. Then

2:28

took her up to her home and got

2:30

her relative to

2:32

give him money, and then left

2:35

and drove her car to another

2:37

location and abandonment. They

2:39

then went through

2:42

photo identification, but trolling

2:44

of photographs and the

2:47

woman identified marrying

2:49

Cokeley. But the amazing thing

2:51

about the case is that he

2:53

had something like fourteen

2:55

fifteen alibi witnesses that

2:58

he was at a prayer service on

3:00

the other side of the bronx. They

3:03

then did conventional prology

3:05

testing of semen. There

3:07

was none of his blood

3:09

type in the prological

3:12

analysis of the semen, so

3:14

in theory he should have been excluded. And

3:18

our friend Bob Scheller, who

3:20

was then head of the prology unit at the New York

3:22

City Medical Examiner's Office, testified

3:25

at the insistence of a prosecutor who

3:27

asked him forceful questions, well,

3:30

isn't it possible that

3:32

he Marrion could have been a low level

3:34

secret Essentially, it would have been a

3:36

false negative on the prology test

3:38

because he didn't secrete enough blood group substances

3:40

into his semen. And so Bob

3:43

said, yeah, in theory, that's true, and that

3:45

was enough to get a guilty verdict

3:47

from the jury. So we

3:50

then went out. We had Marrion frankly

3:53

ejaculate at the random

3:55

intervals and Attica prison to prove that he

3:57

was not a low level secretor. And

4:00

then we said, well, what about the fingerprints

4:03

on the rearview mirror of the car,

4:05

And they said, oh, no, that's not a fingerprint,

4:07

that's a palm print. And in New York City

4:10

we don't do palm prints. So

4:13

we were lucky enough. I had a male nurse

4:15

in my clinic that New Cops, and

4:19

he went up to Attica and rolled

4:21

a palm print of marrying Cokeley

4:24

and then we compared it to the palm print

4:26

taken from the rearview mirror and excluded

4:29

him. And so Judge

4:31

Burton Roberts, who was chief judge

4:33

in the Bronx and was a famous

4:35

district attorney there and a

4:37

character in Bonfire.

4:40

The Vanities book is kind of dedicated

4:42

to him. His Burtness

4:44

as he was called, took a look

4:46

at this and basically vacated

4:49

the conviction. Very it's so fascinating

4:52

for me to hear you describe

4:55

these origin stories, because, as

4:57

you know, last year,

5:00

I did this massive report with your

5:02

colleagues at the Innocence Project when I was in the Brooklyn

5:04

DA's office, just to take stock

5:07

of the first twenty five vacated

5:09

convictions at the Conviction Review Unit in Brooklyn

5:12

and just to see what happened.

5:14

And on the one hand, I hear

5:16

that you identified very early

5:19

what were some of our core principles,

5:21

such as this is a cooperative

5:23

search for truth. But what really

5:26

stands out to me is that in

5:28

that body of twenty five cases,

5:31

I think there was almost nothing about DNA,

5:33

And so you launched this movement because you

5:35

saw potential in this new

5:37

technology to change the face

5:39

of justice, and what

5:41

you put into motion al grew the need to

5:43

rely on DNA. I mean, I can't think of the last

5:46

time we had an application that depended

5:48

on DNA in the Brooklyn conviction

5:50

unit. Because of course, now we use DNA

5:53

during the investigation and trial,

5:56

not just as a tool for exoneration, and

5:59

we've come to look for other mistakes and other

6:02

errors that frankly, are sometimes

6:04

harder to find and to identify bring

6:06

to light because it's not as black and white as science.

6:09

And I want to use this as a launching

6:11

off point to get into the

6:13

real reason. I also wanted to talk to you

6:16

today because it seems to me like

6:18

you've had another vision that is

6:20

dependent on seeing the

6:22

potential for new science,

6:25

new tech to enter the space of

6:27

justice, and this is

6:29

about how we can use big

6:31

data to deal with the problem of police

6:33

credibility. I wonder if you could just

6:35

tell us a bit about this new

6:38

project or ambition that you have,

6:40

well, the proposals

6:42

that we've been putting forward. I would

6:44

like to call the Community Law

6:46

Enforcement Accountability Network. It

6:49

really again began with two

6:52

young women who were in the

6:54

Legal age society. One named

6:56

Julie Ciccolini, who had I

6:59

mean they were paying her there

7:01

as a paralegal, but she was really

7:03

a technologist or data science, and

7:06

a woman named Simpia Conti Cook. Of

7:08

what was fascinating about Conte,

7:11

as she's called, is that she

7:14

had a background, initially as a civil

7:16

rights attorney, so she had

7:18

a sense of patterns

7:20

of misconduct their officers might engage

7:23

in. So they began to build

7:25

a defense database.

7:28

You know, New York had the

7:30

second worst law in the country. The first

7:33

worst law in the country was California

7:35

hiding police misconduct data.

7:38

And this law, we should say, has

7:40

been repealed. You advocated for its repeal.

7:42

I advocated for this repeal. I assume you're referring

7:44

to fifty A. Well, fifty A in New

7:46

York and California that they called it pitches

7:49

and it's not completely gone, but it felt

7:52

first. But what's important

7:54

to know about it is that in New York they started

7:56

this database and so

7:59

they would try to other as much public data

8:01

as they could. So it

8:03

turned out that officer overtime

8:06

was public data. So you could do a freedom of

8:08

informational low request to get the overtime

8:11

data on the police. And that was very

8:13

telling because you know, you could

8:15

really find things out about the

8:17

officers, particularly those ranking up, a

8:20

lot of overtime, where they really were

8:22

where they said they were, but you should watch them.

8:24

That was number one. Number two, they would

8:26

scrape the data of civil rights cases

8:29

brought against New York City police officers

8:32

and they would then put that into

8:34

the database, and then they would

8:37

scrape everything from newspapers

8:39

with the name of the officer. And you

8:41

know, this requires random of information

8:43

acts. Just taking New York City and you have to do

8:46

the CCRB, then you have to do the

8:48

police department, then you have to

8:50

do the prisons, and then the data

8:52

comes in and it's from different years

8:54

and different systems. So how

8:56

do you all get it and how do you work

8:59

with it? And it's very important to emphasize

9:01

that it's what one would call a federated

9:04

database. That is to say,

9:07

they gave it to the

9:09

Bronx Defenders and New York County Defenders,

9:11

the Brooklyn Defenders, a nonprofit like the

9:13

Innocence Project or the NYCLU.

9:16

You could get limited access,

9:18

but each of the different offices had

9:20

information that couldn't be disclosed,

9:23

even things they got under protective order that couldn't

9:25

be widely shared. And let me just interrupt

9:27

you to say, for the sake of our listeners

9:30

that while you are describing this

9:32

database that defense

9:34

counsel are putting together, prosecutors,

9:37

of course have a constitutional, statutory,

9:39

and ethical obligation to

9:41

know their witnesses and to collect

9:44

and then disclose impeachment evidence, evidence

9:47

that might be used to reflect on witnesses

9:49

credibility, including police

9:51

officers. So what is your breakthrough?

9:54

Because this all sounds very twentieth

9:56

century and cumbersome. What

9:58

we eventually realized is

10:01

that the legal aid lawyers had

10:03

more information about the police than

10:06

the district attorneys. In the bottom

10:08

line was these two people

10:10

at le AID invented this database.

10:13

Now I began working on this in California

10:16

ATA. In California, probably the biggest

10:18

source of information was

10:20

the press making Public Record

10:22

Act requests, and there was a coalition

10:24

of forty newsrooms that got together, the

10:27

California Reporting Project, and they

10:29

have begun to request the information.

10:32

So just envisioned this in New York and California.

10:34

Now we are learning about

10:37

misconduct information that's

10:40

a quarter of a century old about

10:42

police officers that nobody ever

10:44

saw that you should have been entitled to

10:46

see. And in all of these

10:49

police shooting cases over misconduct

10:52

cases, whether it was Eric Garner

10:55

in New York City and Staten Island and

10:58

Officer Pantaleo, or Derek

11:00

Shelvin and George Floyd, or

11:02

whether it was a detective

11:05

Van Dyke and the killing of Lacwon

11:07

McDonald in Chicago, you

11:10

name it, all of these cases. When

11:12

eventually the scandals emerge, you

11:14

found out that they all had either

11:17

prior acts of misconduct that we're not public

11:19

or a whole series of allegations against

11:21

them. And I want to

11:24

add something here, Barry, because this has been

11:26

very much on my mind. In

11:28

many of these cases, we have found

11:31

out after the fact that there have been allegations

11:33

of domestic violence or sexual assault

11:36

against the officers. The only police officer

11:38

who was indicted for the death

11:40

of Brianna Taylor had allegations

11:43

like that. And I worry about that a lot because there's data

11:45

that shows right that there is more domestic

11:48

violence who maybe two to four times as high

11:50

in police families as in other families.

11:53

You know, that seems important to know. One has

11:55

been information that's been particularly hard

11:57

to get at. Yes, these things were

12:00

kept secret, but now we have a

12:02

coalition that are

12:04

coming together between public

12:06

defenders, journalists, a CEO. You

12:08

were all going to work together. So the journalists

12:11

will do Public Record Act requests

12:13

get the information and the writer's story.

12:16

Their sources will remain private, but

12:18

the public data that they got

12:21

can go into a public database.

12:24

If the defenders do it and they get

12:26

public data, they can put it into a public

12:28

database, and prosecutors and

12:30

prosecutors, as you and I have talked about,

12:32

prosecutors are well

12:35

positioned to get even more information.

12:37

Everybody would have their own database, but

12:39

when they put the information in, they

12:42

would be commonly coded in tag

12:44

so that the public database and

12:47

the defenders and everybody else you can

12:49

search it. You would be able to do apples

12:51

to apples comparisons, and

12:53

this can lead to really great scholarship,

12:56

really great journalism, really

12:59

great holosing analysis, better

13:01

prosecution because we presumably

13:04

could also benefit from

13:06

searching this database for information about

13:09

our witnesses. It changes everything

13:11

because you decide which

13:13

cases to charge in a better way. The judge

13:15

has a better sense of bail. It's

13:17

ground breaking. There are data scientists

13:20

that know how to use machine learning tools.

13:23

So when I talk about coding and

13:25

tagging the data, you know,

13:27

the key part of it is ingesting it, you

13:30

know, using people to

13:32

try to sort it out and summarize it.

13:34

It's going to take forever. But if you use I

13:37

call ite machine learning tools, but it really is our efficient

13:39

intelligence, and all

13:42

big entities in the world

13:44

use this, you will be able to

13:46

actually get this database

13:49

system going. And you know, it's simple

13:51

things that we realized

13:53

early on at the Innocence Project. What

13:55

happens in this country is when

13:58

a crime is to analyze

14:01

evidence, they give it their own laboratory

14:03

number, and they produced the work. They

14:06

have no idea what happens to the case,

14:08

unless some district attorney later calls

14:11

them up to come testify at some hearing

14:13

or trump and so if something goes

14:15

wrong at the LAB level, how do you

14:17

go back and find the

14:19

defendants? What happened in the case, how do

14:21

you track it down? So the

14:24

LAB number should always be tied to

14:27

the original arrest or accusatory

14:29

instrument number in every jurisdiction in this

14:31

country, so we can find everything.

14:34

I imagine one of the benefits

14:36

of this database you're envisioning is that

14:38

even when an officer moves from one jurisdiction

14:41

to another, one borrowed to another, one

14:44

state to another, all of the information

14:46

we know about him will travel with

14:48

him. Yes, but I want to ask you a question, please,

14:51

because you have referred to this information

14:53

as misconduct information in

14:55

this conversation. I have

14:57

talked about it as information that reflects on

14:59

credit ability. But I read something

15:01

really interesting that you wrote, which

15:04

is, as I understand it, you have said

15:06

that in an ideal world, we

15:09

wouldn't just know where

15:11

a police officer may have done something

15:13

wrong, but also what else we need to know about

15:15

his or her experiences to

15:18

understand how she might be moving through the job.

15:21

So you've talked about wanting to know if

15:23

he has had himself substance

15:25

abuse problems, mental

15:27

health problems. Maybe if he's been exposed

15:30

to let's say, lots

15:32

of really traumatic cases, you

15:34

know, let's say, crimes against children, something

15:36

that would really weigh on a person right

15:39

and fray their their

15:41

nerves or their spirit. So have

15:43

I understood you correctly that ultimately

15:47

you would want us to build out a

15:50

multidimensional understanding of police

15:52

officer witnesses, putting every

15:54

being over inclusive, just putting everything we

15:56

can in this pot. Yes, you

15:58

really want to monitor police officers

16:00

to make sure that they don't handle too many

16:04

traumatic frankly domestic

16:06

violence cases in a row. And they're very

16:08

good questions raised by people

16:10

who want to reconstruct

16:13

policing that maybe they shouldn't

16:15

be involved in those kinds

16:17

of encounters in the first place. But

16:20

certainly the secondary trauma that officers

16:23

experience here, you know, is something

16:25

that if you're trying to run a good police

16:27

department, you've got to keep the track

16:30

of that, you know. I find this actually

16:32

very empathetic, Barry, that you're

16:34

not just like searching for the

16:36

bad apples. Part of what

16:38

you're trying to understand is how we can also

16:40

support the police in understanding that

16:43

their vulnerabilities, their needs, how to make

16:45

sure that if they are experiencing, for example,

16:47

a secondary trauma, that we

16:49

have a handle on that. And

16:53

I'm quite moved by that. Actually,

16:56

oh, thank you. That means it's

16:58

not original to me with me. They've

17:00

done really great studies of

17:04

what about the partners. There are

17:06

networks within police departments, right,

17:08

and you have an idealistic young

17:11

officer, and then he gets or she

17:13

gets involved with the group of

17:15

officers that are breaking the rules, right,

17:18

then you might wind up in a situation where you're

17:21

breaking the rules. There's a lot that can

17:23

be done to turn around policing.

17:26

So I have to ask you what I'm sure you've

17:28

been asked before, which is, how is

17:30

this going to make police officers feel if your vision

17:32

comes to life, Well, they feel unfairly

17:35

tracked, vilified. I

17:37

mean, presumably the idea

17:40

that more information is

17:42

always better means that you can't really vet

17:44

some of the things that will go into this

17:47

database, and nor would you want to. And

17:50

so what do you say to the

17:52

critics who ask you those questions. Well,

17:55

I think that the real issue

17:57

has to do with discipline and police

17:59

department, and it is addition,

18:02

an issue of reconciliation. But

18:04

Barry, I'm asking you something different, because there is

18:06

no doubt that many police

18:08

officers have done some unspeakable

18:10

things and abuses of their authority.

18:13

I have documented some, You have documented

18:16

many. But what about the police officer

18:18

who says, you're putting unadjudicated,

18:21

unsubstantiated allegations

18:24

against me into a

18:26

place now where more people can read

18:28

about them, and it makes me feel demoralized,

18:31

or it makes me feel unsafe, it

18:33

inhibits my ability to do my job,

18:35

and thus it's bad for public safety. We

18:38

have some very interesting data

18:41

Larida. Larida has always

18:44

had an open records process. Any

18:48

adjudication has always been

18:50

known, and they also have a very robust

18:54

police decertification process.

18:56

I have a friend named Phil Pulaski who

18:59

is chief of the tectives in

19:01

Miami Date, and you

19:03

know, we would talk about these kinds of issues

19:05

all the time, and then Phil said, you know, it's

19:08

amazing here the detectives

19:10

are very worried about being

19:13

decertified, and as a consequence,

19:16

they'll do what they're asked to do, you

19:19

know. So, I mean, if the system

19:22

is put in place that's transparent, it

19:24

does have, you know,

19:26

certain determent effects, but you

19:28

ask a tougher question in terms of you know,

19:30

I think the officers. A lot of

19:33

it has to do with police discipline. So let

19:35

me just share with you what I think is the

19:37

best law right now in the country potentially,

19:39

and that is Senate Bill seven thirty

19:41

one in California. Senate

19:43

Bill seven thirty one in California tries

19:46

to create one statewide

19:48

standard for

19:51

getting a license. You know, the

19:54

best thing about the movement to

19:56

professionalized policing should be licensing

19:59

off officers. Right, so you get certified

20:02

to be a police officer to carry a gun,

20:04

you're a license like you're a doctoral lawyer

20:07

or all the other professions that life

20:10

and death are involved. Where we want people to

20:12

be licensed. And then the question

20:15

is, well, how do we adjudicate

20:18

complaints about licensing? So

20:21

the proposal in California

20:23

is that there should be a statewide entity so

20:26

the standards are the same whether you're in a small

20:28

town or a large city, and

20:31

that the commission that oversees

20:34

it should have representatives from the

20:36

community impacted people.

20:38

It should have people from middle ranks

20:40

of police departments, chiefs

20:43

of police departments that had prosecutors,

20:45

that should have defense lawyers, and

20:48

it should have academics, frankly,

20:51

people from different disciplines to

20:54

adjudicate complaints

20:56

about misconduct that could lead to decertification.

21:00

Standard for decertification is

21:02

not just you got convicted of a felony, as

21:04

it is so many states, but having

21:06

to do with your fitness to be an officer right

21:09

parallel to other professional licensing

21:11

Exactly, you get due process too

21:14

because they

21:16

can bring a complaint, This entity

21:18

can make a finding right, and

21:20

then you get a hearing in front of an

21:22

administrative law judge where you can protest

21:25

that it doesn't fit the standards

21:28

that have been laid down and defend yourself. And

21:30

it's outside of the collective bargaining

21:32

process. And this is a way

21:34

to really change policing in America.

21:37

You once said very provocatively that

21:40

you thought that big data should be able

21:42

to end test a lying. Is

21:44

this what you meant? Is it this collection

21:46

of data that you thought could end that

21:48

problem of police officers lying

21:51

under oath? Yes, I

21:53

do believe that

21:55

that's true. In this era of big

21:57

data, we should have access to people's training

22:00

scripts, we should have access to related

22:02

type cases that they've gone through, because

22:06

you know, the fact of the matter is that you

22:09

know, once you're a police officer and

22:11

you know you're somebody's

22:13

got to get time off, you'll testified

22:15

that you saw the gun, or you'll testify

22:18

that you made the recovery, or you'll testify as

22:20

some small fact, which in the gram scheme

22:22

of things, seems like a white lie, right,

22:25

and not a big deal. It is a

22:27

very big deal, of course. It's it's aside

22:29

from being wrong, it erodes

22:32

trust in the criminal justice system. It

22:35

is a slippery slope and

22:37

it's a very hard job to be a police

22:39

officer. It's dangerous, it's

22:42

wearing on one psychologically and spiritually.

22:45

I have great admiration and sympathy

22:47

for officers and the law really do we

22:50

share that. But also we

22:52

have to structure their environments.

22:55

It's got to be a place where

22:57

the good police officers are not afraid

22:59

of the battles. I

23:05

will ask you this last question, or maybe you don't want

23:08

to answer it, but we've talked about you

23:11

identifying DNA as

23:13

a way to start ending

23:16

wrongful conviction. Obviously we are not

23:18

there yet, and big data as a way

23:20

to end test allying, and I wonder, if

23:22

you're looking around the corner, Barry, if

23:24

there's another moonshot that you'd

23:26

like to get to at some point. Well,

23:29

I think I think it would be enough to

23:31

start this community law enforcement data

23:33

based system in the United States.

23:36

It would have been enough to start the Innocence Project.

23:39

Well, I think because

23:41

we know that we are at an inflection point

23:43

in criminal justice and we don't know yet

23:45

what to do, it is helpful

23:47

to go back to breakthroughs. And that

23:50

was a breakthrough. I mean, even for me, Why

23:53

did I need to talk to you about the start? I'm

23:55

deeply familiar with the work of the Indicens

23:57

Project, and I think that sometimes

24:00

it's the best way to figure out how to launch is

24:02

to go and see how a previous rocketship actually

24:05

was able to take off. So thank you for telling

24:07

us that story. Well, one day we'll

24:09

have a drink and I'll tell you all the story. But I

24:11

would like to have a drink again, Barry. Yes.

24:20

Hearing is produced in partnership with Pushkin

24:23

Industries. Our producers are Sam

24:25

Dingman and Camille Baptista. Our

24:27

engineer is Evan Viola. Special

24:29

thanks to Malcolm Gladwell and Jacob Weisberg.

24:32

This podcast is paid for by New Yorkers

24:34

for Tally and Barry Scheck's appearance on the

24:36

show does not constitute a political

24:38

endorsement. Please note Barry is

24:40

not speaking on behalf of the Innocence Project

24:43

in this episode. The views he expressed

24:45

today are his own. I am

24:47

running to be District Attorney of Manhattan and

24:49

to set a national example in delivering

24:51

safety, fairness, and justice for all,

24:54

especially are most vulnerable. If

24:57

you like what you've heard, go to Tally FDA

24:59

dot com to learn more about my campaign. I'm

25:01

Tali far Haitian Weinstein. Thank you

25:04

for listening, and I'll see you next time on

25:06

Hearing

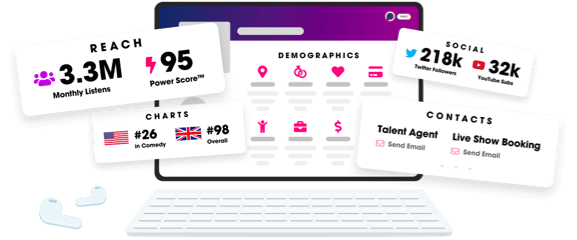

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us